Syndrome extraction cycle in the surface code#

In the previous chapter, we defined the stabilizers for the surface code. Similar to the lessons learned from repetition codes, the data qubits of the surface code can undergo errors (represented by Paulis). The syndromes associated with these errors are obtained by measuring these stabilizers using syndrome extraction circuits.

Logical operators#

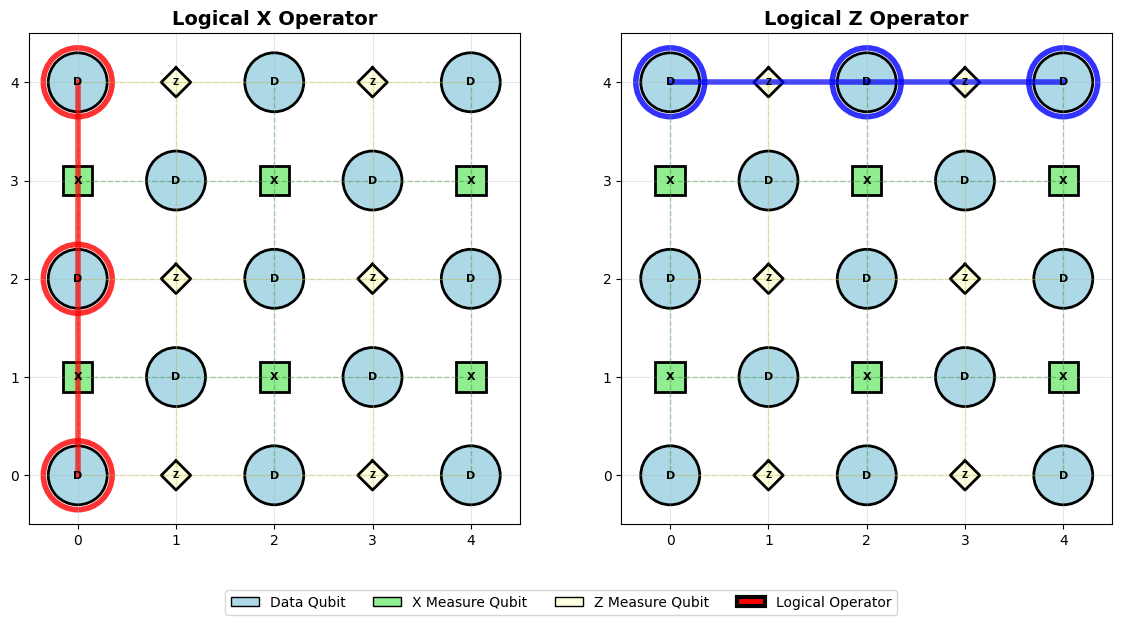

Before we start building, we need to introduce one more important concept — logical operators, denoted as \(X_{\textrm{L}}\) and \(Z_{\textrm{L}}\).

In the 2D surface code, there can be chains of errors that run horizontally or vertically. If these error chains run along the entire length of the surface code, then they are not detected by the code, as they do not trigger any of the surrounding measure qubits. In the literature, this observation is commonly described by noting that these error chains are not part of the stabilizer group, but they still stabilize the code. These error chains incidentally also happen to be the logical operators of the code, analogous to the \(X\) and \(Z\) operators of single qubits.

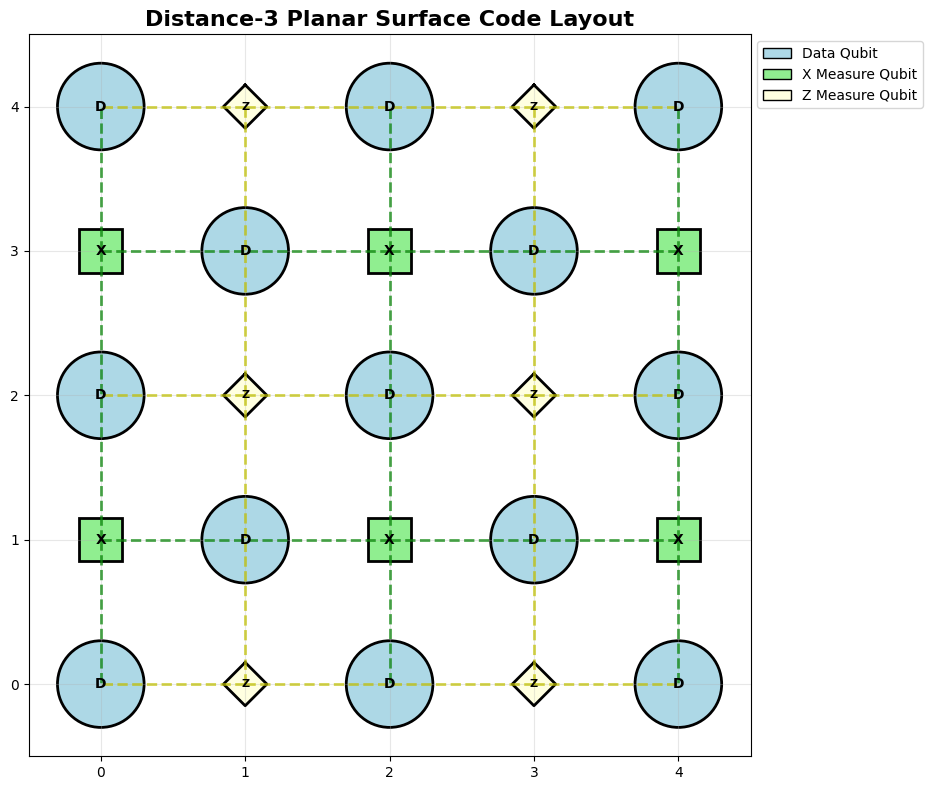

For example, consider the distance-3 surface code below.

PlanarSurfaceCode(distance=3).visualize_layout()

Surface Code Distance: 3

Total qubits: 25

Data qubits: 13

X measure qubits: 6

Z measure qubits: 6

X stabilizers: 6

Z stabilizers: 6

The logical operator \(X_{\textrm{L}} = X_{1} \otimes X_{2} \otimes X_{3}\) runs horizontally from one end of the \(X\)-boundary to the other end (eg rows 0, 2 and 4). Every \(Z\) measure qubit interacts with two data qubits that have \(X\) errors, so the logical operator commutes with all \(Z\) stabilizers in the chain. Hence, applying \(X_{\textrm{L}}\) to the qubit state maps it to a different state outside the codespace, but still stabilized by the codespace — i.e., it produces the same measurement outcome as the original state.

These types of errors are known as logical errors in the surface code, analogous to the repetition code setting. Logical errors are fatal, as they can alter the state of the quantum information stored in the code without being tracked by the stabilizers — and therefore cannot be detected or corrected.

The length of the chain of these logical operators is directly proportional to the code distance. This is why surface codes with larger distances are favorable: they make such errors increasingly improbable. However, we will later learn that simply increasing the distance of a surface code is not always the complete solution. But for now, let’s begin building our syndrome extraction circuits.

Extracting syndromes#

In this section, we will introduce errors to our qubits and measure the corresponding syndromes using syndrome extraction circuits.

We will add on the surface code class we built in the previous notebook by creating a function that generates syndrome extraction circuits. We will also introduce noise to the qubits to be able to observe the syndrome extraction circuits in action.

First, let’s break down the syndrome extraction. As we learnt previously, we are measuring the stabilizers \(Z\otimes Z\otimes Z\otimes Z\) and \(X\otimes X\otimes X\otimes X\). This measurement is done by entangling the measure qubits with the data qubits. We are interested in the final measurement being \(+1,-1\), where the latter value shows that an error has occurred.

The procedure, similar to the repetition code setting, is as follows:

Initialize the measure qubits in state \(\vert0\rangle\) to measure Z-stabilizers and \(\vert+\rangle\) to measure X-stabilizers.

Entangle the measure qubits with the data qubits: a. Measure parity of \(ZZZZ\) to find bit-flip errors. CNOT gates from measure (control) to data qubits (target). b. Measure parity of \(XXXX\) to find phase-flip errors. CNOT gates to measure (target) from data qubits (control). Additionally, apply Hadamard gates before and after the series of CNOT gates.

This syndrome extraction circuit is run for several rounds to allow tracking of errors over time. So essentially, the problem becomes 3D – 2D in space + 1D in time across the repeated rounds. The multiple rounds of syndromes also help to distinguish between data qubit errors and measurement errors.

This brings us to the type of errors we can expect in a syndrome extraction cycle, namely:

Data qubit errors,

Measure qubit errors, and

Measurement errors.

The tracking of these errors over time (multiple rounds of syndrome extraction) is essential to the construction of a decoder graph, which is fed to a decoder. Using an appropriate decoder, the surface code can detect where the error occurred, and apply necessary corrections. We will tackle the decoding process in the next chapter.

Syndrome extraction circuits for distance-3 surface codes#

syndrome_extractor = SyndromeExtraction(distance = 3)

syndrome_extractor.print_syndrome_circuits()

============================================================

X-SYNDROME EXTRACTION CIRCUIT

============================================================

Circuit depth: 8

Total operations: 44

Circuit:

┌───┐ ┌───┐

(0, 0): ────────────X──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│

(0, 2): ────────────┼X─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

││

(0, 4): ────────────┼┼X────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│││

(1, 0): ───R───H────@┼┼─────@──────@───H───M('x_anc_(1, 0)')───────────────────────

││ │ │

(1, 1): ─────────────┼┼─────┼──────X───X───────────────────────────────────────────

││ │ │

(1, 2): ───R───H─────@┼─────┼@─────@───@───H───────────────────M('x_anc_(1, 2)')───

│ ││ │

(1, 3): ──────────────┼─────┼┼─────X───X───────────────────────────────────────────

│ ││ │

(1, 4): ───R───H──────@─────┼┼@────────@───H───────────────────M('x_anc_(1, 4)')───

│││

(2, 0): ────────────X───────X┼┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ ││

(2, 2): ────────────┼X───────X┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────

││ │

(2, 4): ────────────┼┼X───────X────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│││

(3, 0): ───R───H────@┼┼─────@──────@───H───M('x_anc_(3, 0)')───────────────────────

││ │ │

(3, 1): ─────────────┼┼─────┼──────X───X───────────────────────────────────────────

││ │ │

(3, 2): ───R───H─────@┼─────┼@─────@───@───H───────────────────M('x_anc_(3, 2)')───

│ ││ │

(3, 3): ──────────────┼─────┼┼─────X───X───────────────────────────────────────────

│ ││ │

(3, 4): ───R───H──────@─────┼┼@────────@───H───────────────────M('x_anc_(3, 4)')───

│││

(4, 0): ────────────────────X┼┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────

││

(4, 2): ─────────────────────X┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│

(4, 4): ──────────────────────X────────────────────────────────────────────────────

└───┘ └───┘

============================================================

Z SYNDROME EXTRACTION CIRCUIT

============================================================

Circuit depth: 6

Total operations: 32

Circuit:

┌──┐ ┌──┐

(0, 0): ───────────────@─────────────────────────────────────────────────

│

(0, 1): ───R────X──────X─────X───M('z_anc_(0, 1)')───────────────────────

│ │

(0, 2): ────────┼──────@─────@───────────────────────────────────────────

│ │

(0, 3): ───R────┼X─────X─────X───M('z_anc_(0, 3)')───────────────────────

││ │

(0, 4): ────────┼┼───────────@───────────────────────────────────────────

││

(1, 1): ────────@┼─────@─────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ │

(1, 3): ─────────@─────┼@────────────────────────────────────────────────

││

(2, 0): ───────────────┼┼────@───────────────────────────────────────────

││ │

(2, 1): ───R────X──────X┼────X───X───────────────────M('z_anc_(2, 1)')───

│ │ │

(2, 2): ────────┼───────┼────@───@───────────────────────────────────────

│ │ │

(2, 3): ───R────┼X──────X────X───X───────────────────M('z_anc_(2, 3)')───

││ │

(2, 4): ────────┼┼───────────────@───────────────────────────────────────

││

(3, 1): ────────@┼─────@─────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ │

(3, 3): ─────────@─────┼@────────────────────────────────────────────────

││

(4, 0): ────────@──────┼┼────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ ││

(4, 1): ───R────X──────X┼────X───M('z_anc_(4, 1)')───────────────────────

│ │

(4, 2): ────────@───────┼────@───────────────────────────────────────────

│ │

(4, 3): ───R────X───────X────X───M('z_anc_(4, 3)')───────────────────────

│

(4, 4): ─────────────────────@───────────────────────────────────────────

└──┘ └──┘

============================================================

CIRCUIT ANALYSIS

============================================================

X syndrome CNOT layers: 4

Z syndrome CNOT layers: 4

X Layer 1: 6 parallel CNOTs

X Layer 2: 6 parallel CNOTs

X Layer 3: 4 parallel CNOTs

X Layer 4: 4 parallel CNOTs

Z Layer 1: 6 parallel CNOTs

Z Layer 2: 6 parallel CNOTs

Z Layer 3: 6 parallel CNOTs

Z Layer 4: 2 parallel CNOTs

Total X stabilizers measured: 6

Total Z stabilizers measured: 6

Implementing logical operators#

As discussed above, logical operators act non-trivially on the logical qubit state, but since they commute with all stabilizers, they don’t trigger error detection.

The weight of the logical operators are directly related to the distance of the surface code. The code distance is the shortest length of errors that can go undetected.

Logical operators for distance-3 surface codes#

distance = 3 # can change to distance 5

logical_ops = LogicalOperators(distance)

logical_ops.visualize_logical_operators()

============================================================

LOGICAL OPERATORS ANALYSIS

============================================================

Number of logical qubits encoded: 1

Distance: 3

Logical X operators:

X_1: 3 qubits

Path: [(0, 0), (2, 0), (4, 0)]

Description: Vertical string from top to bottom

Logical Z operators:

Z_1: 3 qubits

Path: [(0, 0), (0, 2), (0, 4)]

Description: Horizontal string from left to right

Anticommutation check:

Logical X and Z paths overlap at: 1 qubits

Overlap positions: [(0, 0)]

Anticommutation: Verified

Injecting errors#

To observe the syndrome extraction circuits in action, we will need to inject errors at specific locations. We will enable three different kinds of errors:

Random Pauli errors on data qubits mimicking depolarizing error (randomly choosing one of \(X\), \(Y\) or \(Z\)).

Specifically defined errors at specific positions (eg \(X\) error on qubit at grid location \((i,j)\).)

Logical errors that run from one end of the surface code to another

Injecting errors into distance-3 surface codes#

distance = 3

error_sim = ErrorInjection(distance = distance)

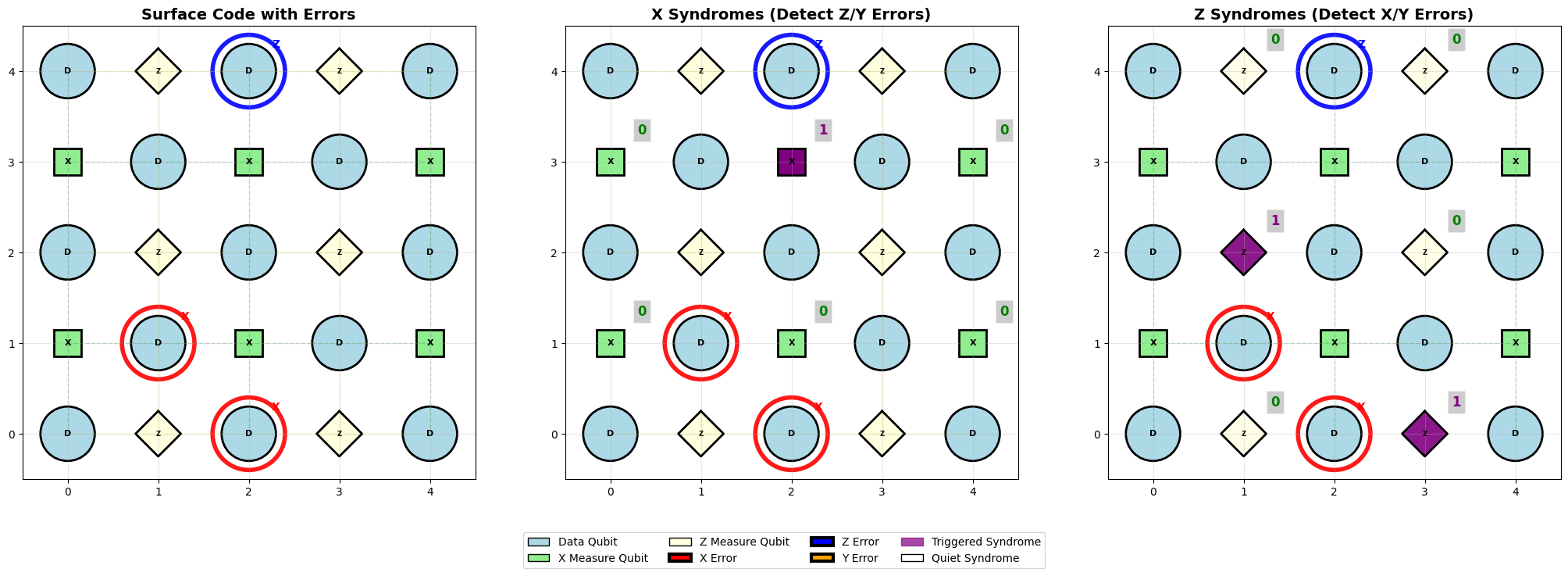

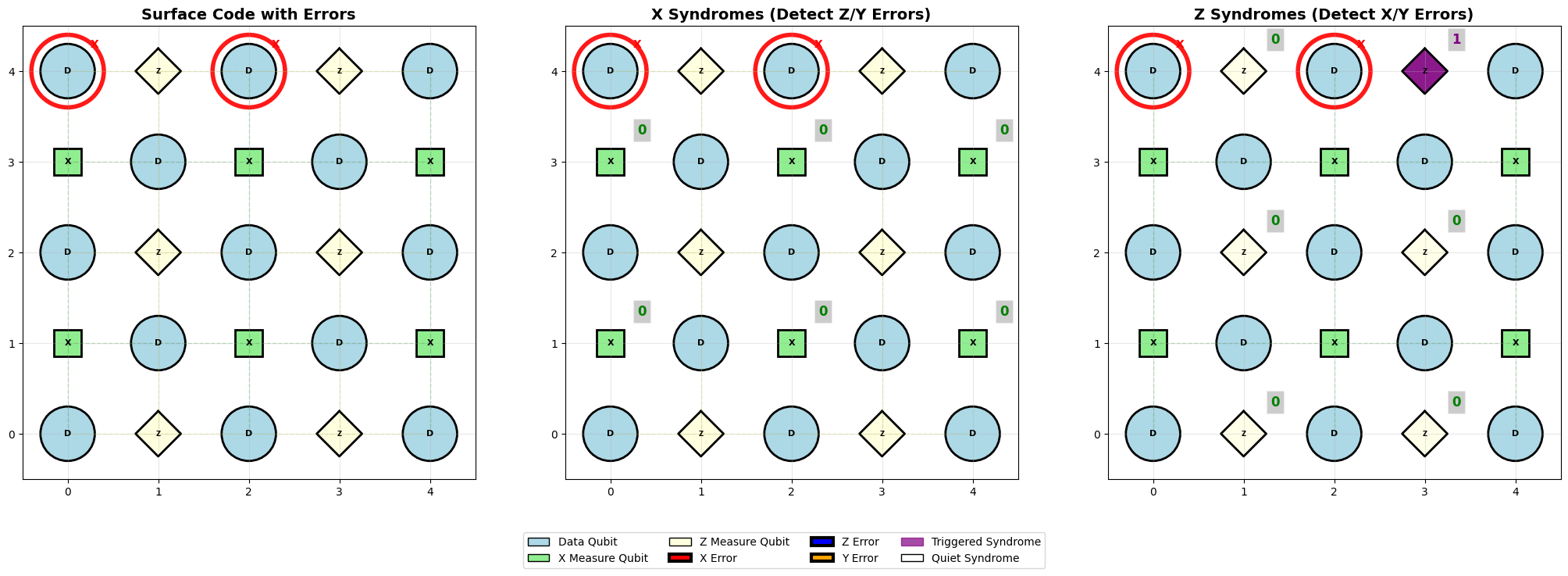

Example 1: Inject random errors and observe the syndrome checks that fire#

error_sim.inject_random_errors(error_rate=0.05, seed=42)

error_sim.visualize_errors()

Errors with rate 0.05:

X errors: 2 at positions [(3, 1), (4, 2)]

Z errors: 1 at positions [(0, 2)]

Y errors: 0 at positions []

Total errors: 3

============================================================

SYNDROME MEASUREMENT RESULTS

============================================================

X syndromes: 1/6 triggered

Z syndromes: 2/6 triggered

Triggered X syndromes (detect Z/Y errors):

Measure qubit at (1, 2): syndrome = 1

Triggered Z syndromes (detect X/Y errors):

Measure qubit at (2, 1): syndrome = 1

Measure qubit at (4, 3): syndrome = 1

Logical flip analysis:

Logical X operator: 0 errors

Logical Z operator: 0 errors

Logical X flipped: No

Logical Z flipped: No

No logical flips

Example 2: Inject even or odd errors in a chain#

When we inject an odd number of errors in the logical path, they do not commute with the logical operator. For example, let’s imagine that the logical operator \(Z_L\) is \(Z_L = Z_1Z_2Z_3\). That means

If an \(X_1\) error is injected, then the logical state \(\vert\psi\rangle_L\), becomes \(X_1\vert\psi\rangle_L\). Now, this new state is related to the logical operator differently:

and we see that it is now an \(-1\) eigenstate of \(Z_L\). This implies that the logical state \(\vert\psi\rangle_L\) has flipped, and it is now the opposite eigenstate of the logical operator with eigenvalue \(-1\).

Similarly, when we inject an even number of errors in the logical path, they commute with the logical operator, with does not lead to a logical flip.

# Inject 1 X errors along logical Z operator -- no logical flip ()

logical_z_path = error_sim.logical_z_operators[0]

error_positions = logical_z_path[:1]

error_sim.inject_specific_errors(x_positions=error_positions)

error_sim.visualize_errors()

Specific errors introduced:

X errors: 1 at positions [(0, 0)]

Z errors: 0 at positions []

Y errors: 0 at positions []

============================================================

SYNDROME MEASUREMENT RESULTS

============================================================

X syndromes: 0/6 triggered

Z syndromes: 1/6 triggered

Triggered X syndromes (detect Z/Y errors):

Triggered Z syndromes (detect X/Y errors):

Measure qubit at (0, 1): syndrome = 1

Logical flip analysis:

Logical X operator: 0 errors

Logical Z operator: 1 errors

Logical X flipped: No

Logical Z flipped: Yes

LOGICAL FLIP DETECTED!

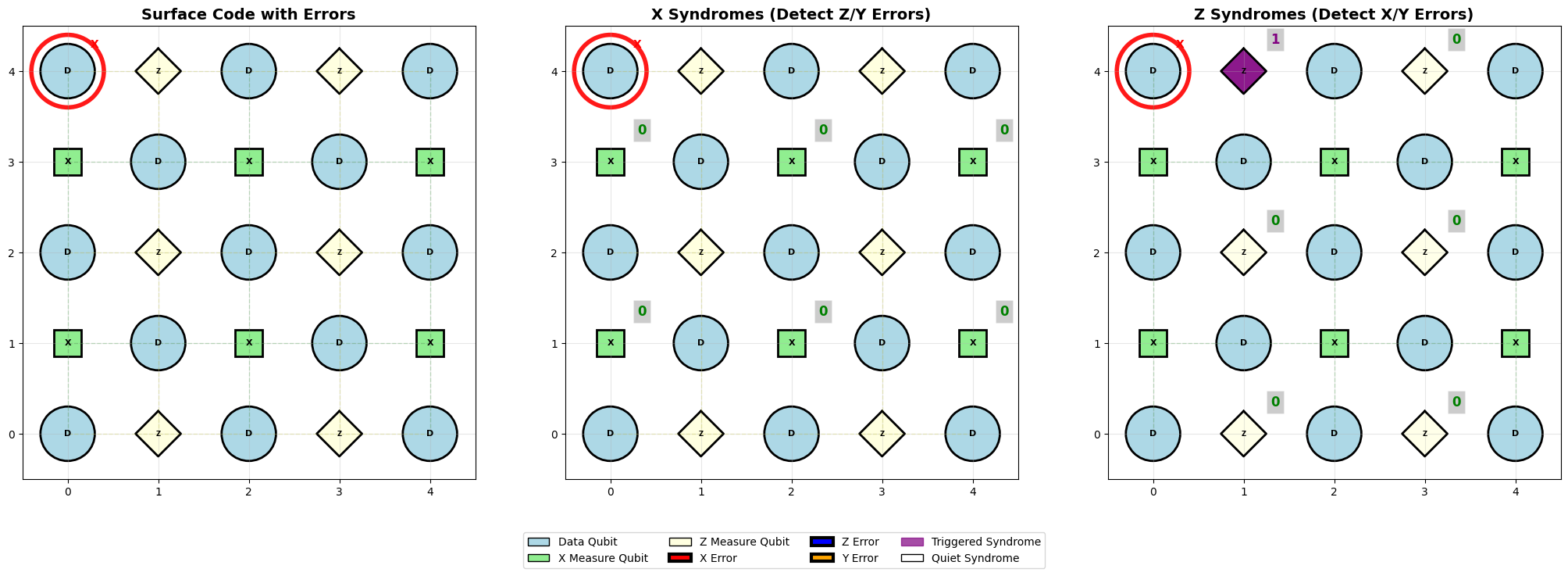

# Inject 2 X errors along logical Z operator -- no logical flip

logical_z_path = error_sim.logical_z_operators[0]

error_positions = logical_z_path[:2]

error_sim.inject_specific_errors(x_positions=error_positions)

error_sim.visualize_errors()

Specific errors introduced:

X errors: 2 at positions [(0, 0), (0, 2)]

Z errors: 0 at positions []

Y errors: 0 at positions []

============================================================

SYNDROME MEASUREMENT RESULTS

============================================================

X syndromes: 0/6 triggered

Z syndromes: 1/6 triggered

Triggered X syndromes (detect Z/Y errors):

Triggered Z syndromes (detect X/Y errors):

Measure qubit at (0, 3): syndrome = 1

Logical flip analysis:

Logical X operator: 0 errors

Logical Z operator: 2 errors

Logical X flipped: No

Logical Z flipped: No

No logical flips

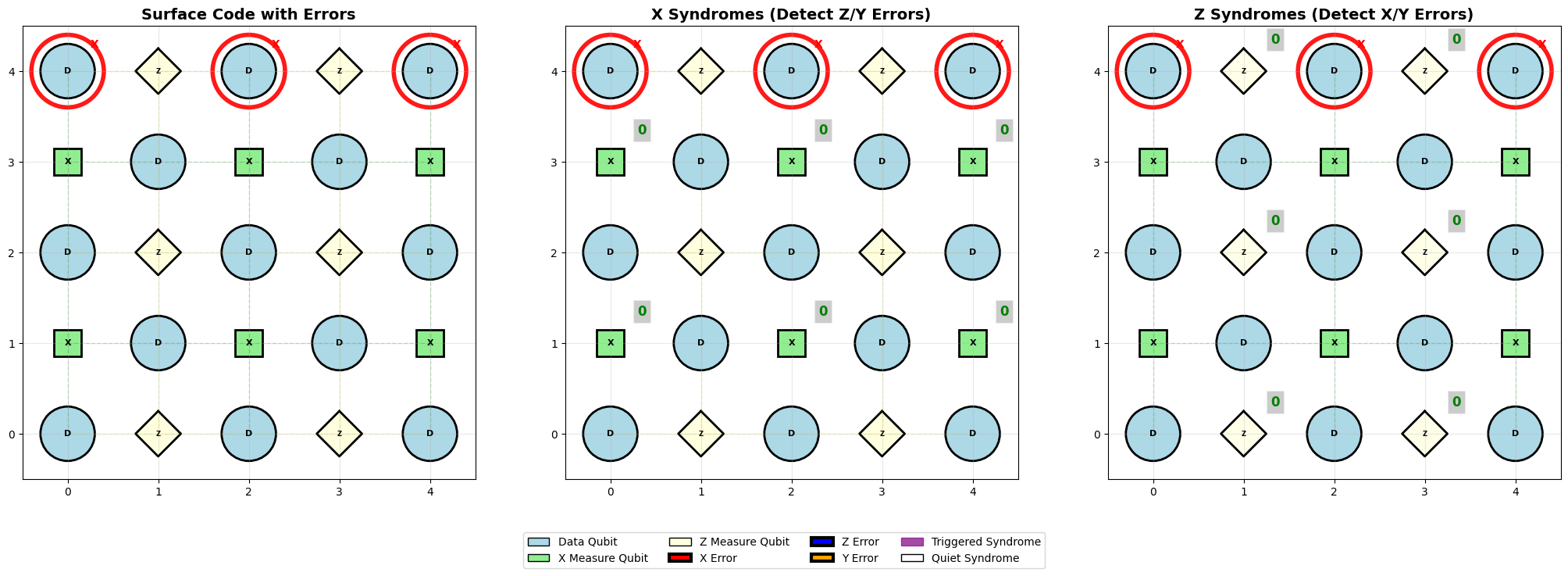

# Inject 3 X errors along logical Z operator -- logical flip since end to end

error_positions = logical_z_path

error_sim.inject_specific_errors(x_positions=error_positions)

error_sim.visualize_errors()

Specific errors introduced:

X errors: 3 at positions [(0, 0), (0, 2), (0, 4)]

Z errors: 0 at positions []

Y errors: 0 at positions []

============================================================

SYNDROME MEASUREMENT RESULTS

============================================================

X syndromes: 0/6 triggered

Z syndromes: 0/6 triggered

Triggered X syndromes (detect Z/Y errors):

Triggered Z syndromes (detect X/Y errors):

Logical flip analysis:

Logical X operator: 0 errors

Logical Z operator: 3 errors

Logical X flipped: No

Logical Z flipped: Yes

LOGICAL FLIP DETECTED!

Recap#

Let’s recap what we have learned so far.

We introduced the planar surface code, and how the data and measure qubits are laid out.

We built syndrome extraction circuits to measure stabilizers using the measure qubits. These circuits were analogous to those used with repetition codes but are carefully arranged since the surface code is a 2D setup.

We learned about logical operators.

We simulated syndrome extraction circuits using simple noise models.

We visualized the errors on the planar surface code.

Next steps#

We used a very simplistic noise model to demonstrate syndrome checks in action. However, in practice, you would use a noise model that more closely resembles the measured qubit noise on the real quantum system in consideration.

In the next section, we will learn how to decode these errors and make plots that show the code threshold, similar to the journey with repetition codes in earlier chapters. Instead of building this functionality ourselves, we will start using stim and implement our work using the rotated surface code. stim can automatically generate the syndrome extraction circuits for us, and we will use the detector error model from stim to decode errors using pymatching.

Version History#

v0: Aug 14, 2025, github/@ESMatekole

v1: Sep 12, 2025, github/@aasfaw

v1: Sep 16, 2025, github/@aasfaw edits incorporating feedback from Ophelia Crawford