Unrotated surface codes: layout and stabilizers#

In this notebook, we will visualize the surface code embedded on a 2D nearest-neighbor grid with data qubits and measure qubits. As you have learned before, we cannot directly measure the data qubits. As before, in order to detect X and Z errors on the data qubits in such a grid, we will measure a set of measure qubits. As a reminder, these are known as stabilizer measurements, and the operators measured are called stabilizers.

The stabilizers for the surface code we are about to build are \(Z\otimes Z\otimes\ldots\otimes Z\) and \(X \otimes X\otimes\ldots\otimes X\).

This chapter is based on Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation.

The layout of the unrotated surface code#

We will consider the unrotated planar surface code with open boundary conditions. The qubits are arranged on a 2D lattice. Below, we create a Python class for the planar surface code. You can expand the code cell below to see how it works.

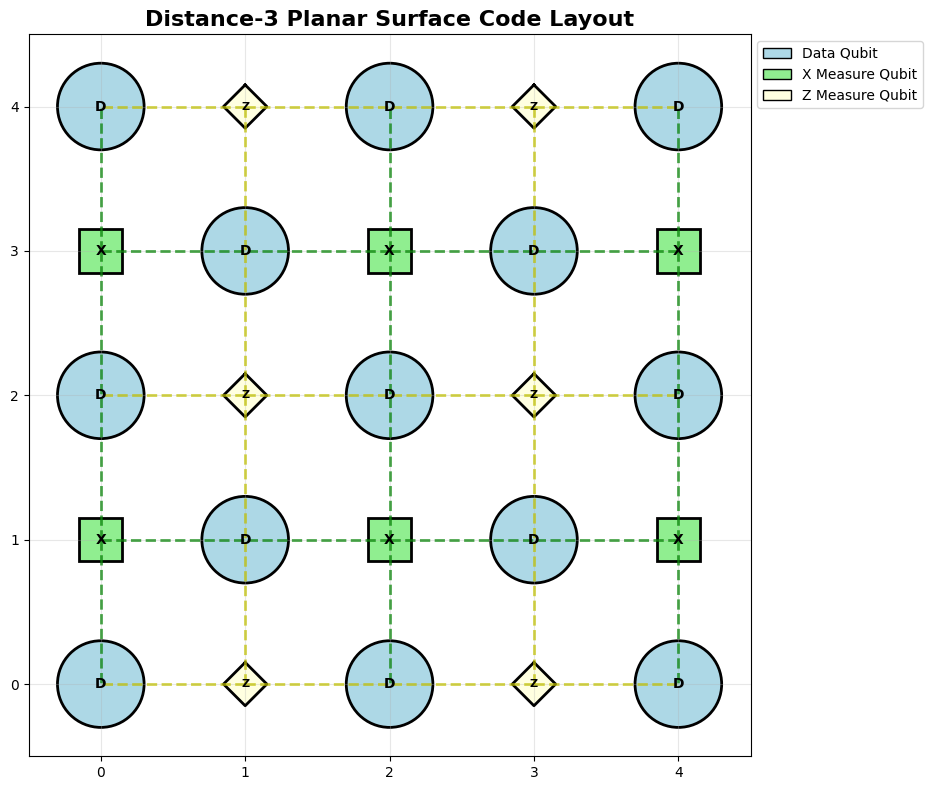

We can draw an unrotated surface code of distance 3 as follows. Note that the layout has 25 total qubits, with 13 data qubits and 12 measure qubits.

distance = 3

surface_code = PlanarSurfaceCode(distance)

surface_code.visualize_layout()

Surface Code Distance: 3

Total qubits: 25

Data qubits: 13

X measure qubits: 6

Z measure qubits: 6

X stabilizers: 6

Z stabilizers: 6

In the figure above, the data qubits away from the boundary have four neighboring measure qubits, while those at the boundary can have two or three measure qubits.

In the bulk of the surface code, each data qubit is connected to two \(Z\)-measure qubits and two X-measure qubits.

A \(Z\)-measure qubit forces its neighboring data qubits into the eigenstate of the \(ZZZZ\) operator. Similarly, an \(X\)-measure qubit forces its neighboring data qubits into the eigenstate of the \(XXXX\) operator.

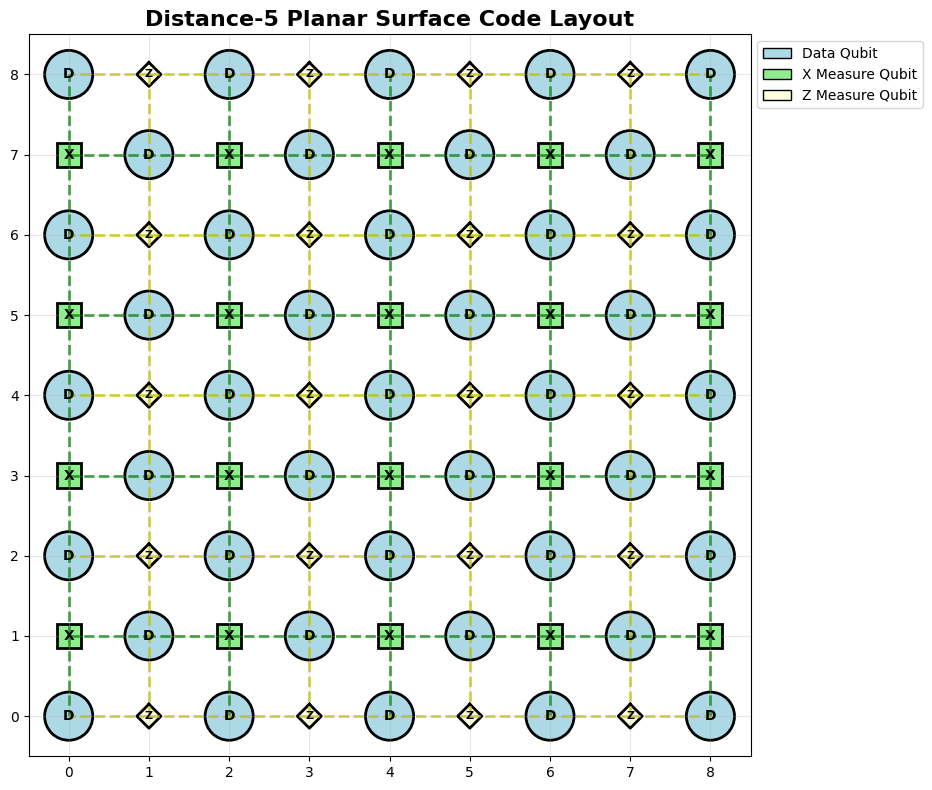

surface_code = PlanarSurfaceCode(distance=5)

surface_code.visualize_layout()

Surface Code Distance: 5

Total qubits: 81

Data qubits: 41

X measure qubits: 20

Z measure qubits: 20

X stabilizers: 20

Z stabilizers: 20

The rotated surface code#

The unrotated surface code above is an example of a \([[n,k,d]]=[[(d^2+(d-1)^2),1,d]]\) stabilizer code. A distance-\(d\) surface code encodes one logical qubit using \(d^2+(d-1)^2\) physical qubits. The unrotated surface code is made up of a total number of \(d^2+(d-1)^2 = 2d^2-2d+1\) data qubits and \(2\times d\times(d-1) = 2d^2-2d\) measure qubits, for a total of \(4d^2-4d+1\) physical qubits.

There exists another flavor of surface code known as the rotated planar surface code (\([[n,k,d]]=[[(d^2,1,d]]\)). As the name suggests it is a rotated version of the planar surface code by an angle of \(45\) degrees. The main advantage of the rotated surface code is that it requires fewer physical qubits (\(d^2\) data qubits and \(d^2-1\) measure qubits for a total of \(2d^{2}-1\)), saving the need for an additional \(2d^2-4d+2\) physical qubits over the unrotated variant.

For additional analysis of the comparison between the two variants, refer to Compare the Pair: Rotated vs. Unrotated Surface Codes at Equal Logical Error Rates.

Exercise for the reader: Modify the Python code above for the unrotated surface code to visualize the rotated variant!

Now that you are familiar with the layout of the surface code, we will start to understand logical operators on the surface code and create circuits that will measure the respective stabilizers. We will learn the meaning of code distance and how it relates to the logical operators.

Version History#

v0: Aug 14, 2025, github/@ESMatekole

v1: Sep 12, 2025, github/@aasfaw